My first ever job out of university was as a B2B technology copywriter for a marketing agency. I wasn’t from a tech background (I did English as an undergrad, then Journalism as a postgrad), but when a recruiter asked me if I fancied getting into the sector, I thought “go on, why the hell not”.

In my first few months I struggled to understand what IT companies were actually saying in marketing collateral. I found the way that marketers talked about IT to be unclear, verbose and unnatural — in equal measures. I might as well have been reading Greek. But for the life of me, what I really couldn’t get my head around, was why those working in communications couldn’t communicate in plain English. The irony fascinated me.

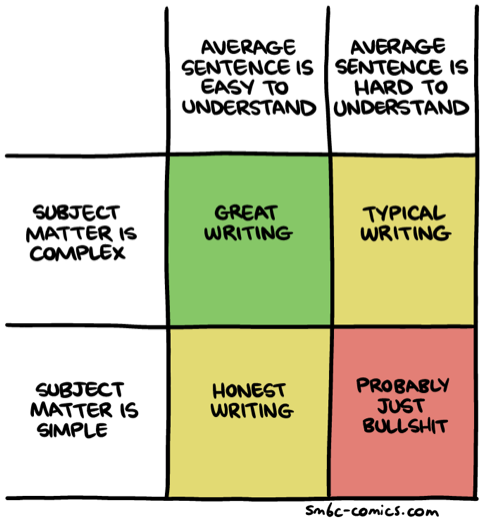

It was a steep learning curve in my first few months of technology copywriting, but I was encouraged to write about technology in a way that anybody could understand. Be clear and concise. Be simple but not simplistic. No-one’s ever going to complain if you make something easy for them to understand. And I lived and died by this quadrant:

Now I work in PR, and I’ve tried to bring most of those skills with me and spread the good word of “great writing”. However, outside of Wildfire, I see more and more examples of writing in that bottom right quadrant every day, and I’ve convinced myself there are two reasons for it.

Number one — people think that writing is easy because they used to do it all the time at school and university. So when some of the brightest technical minds turn to writing, they can often forget that they understand more about their particular topic than everyone else, so their copy can often be confusing to the outside world. Filtering your messaging through a copywriter — ideally a complete outsider to your business and industry — can often help distil concepts into something much clearer and much more powerful.

The other reason, perhaps more cynically, for poor writing is that people often like sounding cleverer than they really are. There’s even been empirical research into confusing language — finding that the vaguer the language you use, the more powerful you seem to your colleagues and employees.

And since I can’t write a stiff letter complaining to the IT world, I’ve done the next best thing, which is to write a blog post about it.

So, here’s what really grinds my gears.

1. Pretentious and unnatural phrasing

There seems to be this myth that anything written down needs to be more formal than speech. Too many a time have I seen the phrase “gain cost savings and time” on an IT company’s website or in a white paper. What’s wrong with “save time and money”? No-one actually says “gain cost savings and time” out loud, so why write it down?

You know there’s a problem when non-natural phrasing starts spreading to informal settings. A sales director at an IT company once described to me in the pub that the beer he had on a Prague stag do was “cost effective”. Who describes beer as “cost effective”?

2. Unclear meaning

In another example, I asked a colleague, who’s worked in IT PR for seven years, what “the democratisation of data” meant. I’d read articles about it in Forbes, Computer Weekly, ITProPortal, Computing and other reputable publications, and it’s a phrase that, for me, was an instant turn off. She looked at me as if I’d gone mad — she’d never heard of it. “Nobody actually uses it, do they?”

After reading about the topic, I’ve deduced it pretty much means “making data available to the end user”. I’m at a loss as to why the IT industry can’t just say that. “Democratisation of data” sounds like something @managerspeak would jump on. Either that or perhaps the IT industry has adopted the Sir Humphrey Appleby ‘clarification-through-obfuscation’ approach to communications:

3. Exclusive language

Basically jargon. You know the type — it’s either a word you’ve never heard of or an acronym with no explanation. If you understand it, great, but if you don’t, you’re completely left behind. It’s like a private members club for language. It beggars belief that people still use jargon, even if their target audience understands what it means. Speaking in plain English helps improve public perception of your work and helps improve customer relationships.

4. The new standard

Often non-standard English becomes standard through years of misuse — usually when the Oxford English Dictionary caves and amends its records based on enough public usage. It’s a bit of a bugbear of mine but that’s exactly what has happened with the rise of “on-premise” over “on-premises”, which has come about through a trend called hypercorrection (a misunderstanding on a point of grammar).

Plain English won’t alienate audiences

Yes, there’s an argument to suggest that we need to communicate in the same language as those to whom we’re communicating — and of course we don’t want to alienate audiences. But most people understand plain English whatever industry they work in, so why not communicate in plain English? If you truly want copy that delivers “cut-through” (yuck), get a writer who makes something complex sound easy. You won’t do that with sentences longer than 50 words a pop containing more clauses than I can shake a stick at.

In the words of a former client of ours: “Life is simple. We do our best to complicate it.” Say what you mean, mean what you say, and write about technology in the way you’d explain it down the pub with your mates.

“Dropping the Buzzwords from our Profiles” – new cartoon series collaboration with @LinkedIn https://t.co/n1s3BWQc69 pic.twitter.com/HoDKX9PPhm

— Tom Fishburne (@tomfishburne) January 20, 2016