Technology has never been more capable of bringing people together. The social media explosion emerging from the streets of Hong Kong is the most recent example of people harnessing connectivity and tech to enact genuine change.

At the same time, it brings together people that are fundamentally different. China’s tendency to detain social media critics is not without logic; Donald Trump’s Twitter activity has fast become a tedious, clichéd way of using tech to divide, differentiate and demean. People are often uncomfortable when connected with people who aren’t like them.

The media landscape, from Brexit to Iran, would have you believe that these divisions are worse than ever. But tribalism has been an obstacle for us since time immemorial; we’re just more aware of it.

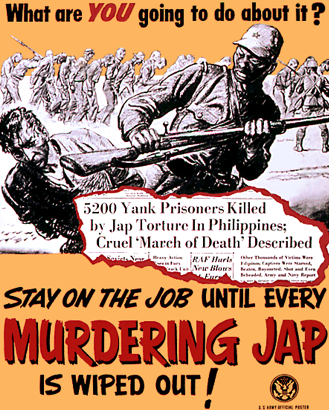

‘Othering’ groups of people — emphasising the ‘irreconcilable’ differences between the ‘them’ and the ‘us’ — is one of the oldest political tools we know, and technology has often been a weapon in this fight. Traditional orientalism is the perfect example; the ways in which the western world doggedly differentiated itself from eastern cultures as more civilised, more moral, or simply superior.

Orientalism was at its peak immediately after World War II. The vicious combat involved of the Pacific had given the Japanese a reputation as savage, animalistic, zealous self-martyrs to westerners. Japan’s defeat through the atomic bomb, morality aside, was an incredible demonstration of technological superiority. It served as ‘proof’ to westerners that they were better than the ‘others’.

In the post-war era, the Japanese upended this caricature. The industry sparked by the Korean War kickstarted Japan’s economy, with its GNP growing at a 10% throughout the 1960s and a 5% in the 1970s. When it levelled out in the 1980s, Japan had fully established a high-wage economy.

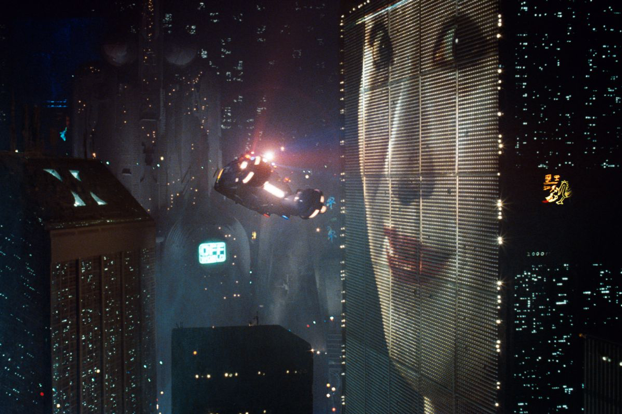

As a response, traditional orientalism gave way to techno-orientalism. Given Japan’s economic and industrial prowess, the animalistic parodies of WWII couldn’t apply any more. A new prejudice, driven by a fear of Japan’s economic and industrial superiority, portrayed its people as sacrificing personality and freedom in the name of efficiency and machines.

This image permeated swathes of western pop culture in the 1980s and ‘90s. Blade Runner’s incredible backdrop is both intimidating, dystopian, and very Japanese. Both versions of Ghost in the Shell’s cyborg protagonist embody the stereotype of western beauty and yet have been constructed, as though the orient couldn’t produce it naturally.

As it turns out, such prejudice was a knee-jerk reaction — who knew?! — as hypocritical as it was premature. Japan’s economy suffered a downturn in the 1990s, and brands like Sony and Toyota were increasingly assimilated into western countries. The inhuman machine was suddenly seen as a bumbling nation without much economic direction, even if it happened to make great cars and stereos.

Western suspicions softened as a result, and as technology has permeated our lives, the ‘othering’ of Japan has increasingly dissolved. The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami is a tragic but poignant example. The costliest natural disaster in history at US$235bn and the claiming of over 15,000 lives received immense coverage in the west.

Humanitarian efforts from all over Europe and America came to the nation’s aid. Interestingly, hysterical US clickbait peddlers waved at (incorrect) maps showing the potential spread of radioactive material. Japan’s problem was suddenly their problem too.

Techno-orientalism is fascinating both in the way that it weaponised technology as an alienating force, and in the way that we can look back on it as a product of the political and cultural landscape at the time. Misgivings about other cultures will always feel more justified without the gift of hindsight. When we wade into battle with other keyboard warriors about today’s issues, that’s worth remembering.